“I had the privilege of witnessing it in person and just the atmosphere on the ground was, for want of a better term, electric,” said David Sercombe in an interview with the Tech Zero podcast.

Sercombe is the head of the technical team at MagniX, the company that provided the electric propulsion system that enabled the Eviation Alice to make that groundbreaking flight through Washington State airspace on September 27.

Alice was not the first plane to fly with an electric motor rather than one powered by fossil fuels; single and double-seater electric aircraft made by Slovakian company Pipistrel have already flown through Australian airspace. But with room for 11 people to ride, Alice is believed to be the biggest.

“It’s definitely a significant milestone in the electrification of aviation,” Sercombe told Tech Zero.

“This [Alice] is unique in a number of different realms. Firstly, it’s the largest all electric plane to fly. Secondly, it’s the first of that size to be designed from the ground up to be electric. It’s not a retrofit, the whole airframe was designed to take advantage of the benefits of electric propulsion.”

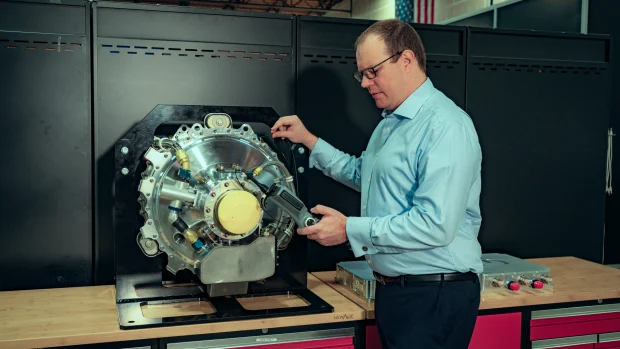

Toowoomba-raised David Sercombe is making waves in Seattle with a world-leading electric aviation motor. Photo: Geo Rittenmeyer

Decarbonising aviation is a gigantic task. Just as battery technology is not yet capable of powering the big cargo ships that sail the world’s oceans, nobody expects the big commercial aircraft that carry hundreds of people at a time to go electric any time soon.

Big airlines like Qantas, British Airways, United Airlines, Singapore Airlines and Emirates are more focused on finding low-carbon fuels that can power their jets without forcing a big change to fuel tanks and other equipment.

“The battery technology is not going to support an all-electric 737 [commercial aircraft] any time in the near future. I think that’s a fairly safe statement to make,” says Sercombe.

“Although I’m a bit of a technology optimist. I like to see the possibilities for the future. It all depends on the time frame that you look over.

“For the larger aircraft, we’re going to be looking at more electrification – so, in other words, it’s not full-battery electric plane, but, you know, more and more electric elements are creeping onto it, and maybe some hybridisation.

“I expect that [by] the back end of this decade, we’re going to start to see the take-off, pun intended, of electric aviation.”

Alice eclipsed the 2020 flight that MagniX was involved in at the same airport, where a nine-seater Cessna Caravan was retrofitted with an electric propulsion system.

Like many of the world’s cutting-edge aviation and aerospace companies, MagniX is based in the northern suburbs of Seattle. Yet many of its staff speak with Australian accents.

That’s a legacy of the company’s origins on the Gold Coast, where it was known as Guina Energy after its founder Tony Guina set up a company in 2005 that aimed to design lighter and more powerful motors.

The company moved to the US in 2017 and rebranded itself MagniX.

Most advanced in the world

It has used superconducting technology, permanent magnets and a unique engine cooling system based on liquid in a closed loop to create a powerful, lightweight motor that can work at altitude, putting it at the front of the queue for the airlines that want to go electric, including several in Australia.

MagniX will supply the propulsion systems to Dovetail Electric Aviation, a joint venture created over the past year by Rex Airlines, Sydney Seaplanes and Spanish company Dante Aeronautical.

“MagniX, to our understanding, are the most advanced electric aviation motor manufacturer in the world at the moment and the closest to certification,” said Dovetail co-founder Aaron Shaw, who is also chief executive of Sydney Seaplanes.

The benefits of flying with an electric motor and battery are analogous to those that motorists enjoy when they switch to an electric vehicle; the planes are quieter, emit fewer greenhouse gases, and are cheaper to run in the short term because fuel is eliminated.

Shaw believes they will also be cheaper to run in the long term because their lifespans will be three times longer, thereby delaying the normal engine replacement cycles.

But Shaw told Tech Zero that electric motors will initially cost more to buy, and there will be other compromises, too.

“The weight of the batteries is going to be something that reduces the payload or the range of that aircraft versus a fuel-powered aircraft,” he said.

“Jet fuel has about six times as much energy per kilogram than the best tech battery we’ve got.

“It’s pretty major mindset change from the point of view of pilots and operating these aircraft; the weight doesn’t change throughout the flight, you’re not burning anything off.

“A lot of aircraft have a maximum take-off weight and a maximum landing weight, and they can be different because the expectation is that you’re reducing your weight in flight.

“What that means is that when you certify an aircraft for battery-only flight, then you might have to beef up the landing gear as well as part of that process.”

Alice flew for only eight minutes on September 27, but Sercombe says sceptics should not assume that was its full range. “Certainly, it’s capable of more,” he told Tech Zero.

“That flight profile was about demonstrating aircraft handling aspects, confirming from our side that the propulsion system behaved precisely the same in the air as it did on the ground.”

The customers for MagniX’s technology – and electric planes in general – tend to be owners of small aircraft, such as those that Sydney Seaplanes uses to carry tourists on joy flights, or the small planes that Rex uses to fly to regional towns.